There’s an imaginary line that circles our planet. It’s a border, of sorts. It runs from pole to pole. Not a national border or country frontier, but its impact is just as profound to those countries that find themselves on either side of it. In order to understand why this line is so weird, and why it exists at all, we need to travel back to 1675 and half a world away to sleepy Greenwich and the establishment of the Royal Observatory.

The Royal observatory is an entire subject to itself, but it’s important to understand the impact that the observatory has had on world geography. For mariners and geographers before 1675, Latitude was a well understood concept. The earth was divided into 2 hemispheres with a line running exactly between the two. We know this line as the equator. Two additional lines of latitude were added in the form of the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn. These are the two points at which the sun reaches its highest declination. Basically the point at which the sun can be seen directly overhead at its solstice

Up until the foundation of the Greenwich observatory, there was no obvious line that longitude should run along. Amongst the many other things that the observatory was responsible for was the creation of the Prime Meridian.The Prime Meridian, which passes through Greenwich, was designated as 0° longitude. Run that line around the entire globe, bisecting the poles and, located at 180° longitude, you will find the International Date line (IDL). Its primary function is to accommodate the Earth’s rotation and the 24-hour day cycle, ensuring that when you cross it, the date changes by one day. Crossing from west to east results in going back a day, while crossing from east to west moves you forward by a day. So far, so simple, but from this fact onwards, international geography starts to take a back seat to international politics.

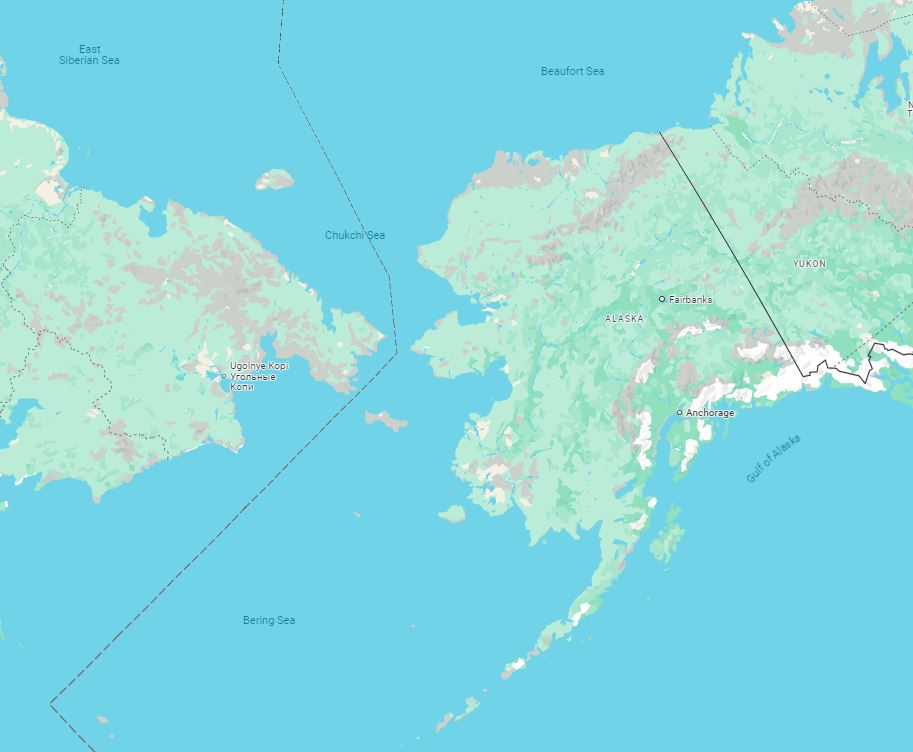

The Northern Reaches: The Arctic Ocean

Head due south from the north pole along the international date line and the first land you hit is Wrangel Island, and the Russian Okrugs (Autonomous district) of Chukotka, if the IDL were to maintain a straight line it would move this district to the east of the IDL and separate it from the rest of Russia by one whole day. Further south, parts of the Alaskan Aleutian islands would suffer the same fate in the opposite direction. This was unacceptable to both countries. Here we have our first of many instances of geopolitics. The line bends, first east across the Chukchi sea and into the Bering strait.

It dissects the Diomede islands, which, despite being just over 2 miles apart, are separated by a whole calendar day. Big Diomede, belonging to Russia being one calendar day ahead of little Diomede, which belongs to the USA. This unique situation often earns the islands the nickname “Tomorrow Island” (Big Diomede) and “Yesterday Island” (Little Diomede).

Once through the Bering strait, the date line takes a sharp turn to the west, ensuring that the St Lawrence island, and the entirety of the Aleutian archipelago remain on the same side of the line as the rest of Alaska. I think we can all agree that these minor deviations to maintain territorial integrity are fine. The deviations around Russia and USA caused roughly a 10° deviation first to the east, and then to the west of the IDL before settling back onto the correct longitude of 180° just south of Alaska.

The Northern Pacific Ocean

For the next 5,500km, the IDL behaves itself. The line runs due south and encounters nothing but the depths of the pacific. The nearest it comes to anything at all is roughly 2,000km into it’s journey, when it passes Midway Atoll, venue of the famous world war 2 naval battle, roughly 250km to its east. By the time we reach the equator we’ve done literally half the globe with just minor deviations to avoid splitting countries in half. It’s at this point that things get interesting.

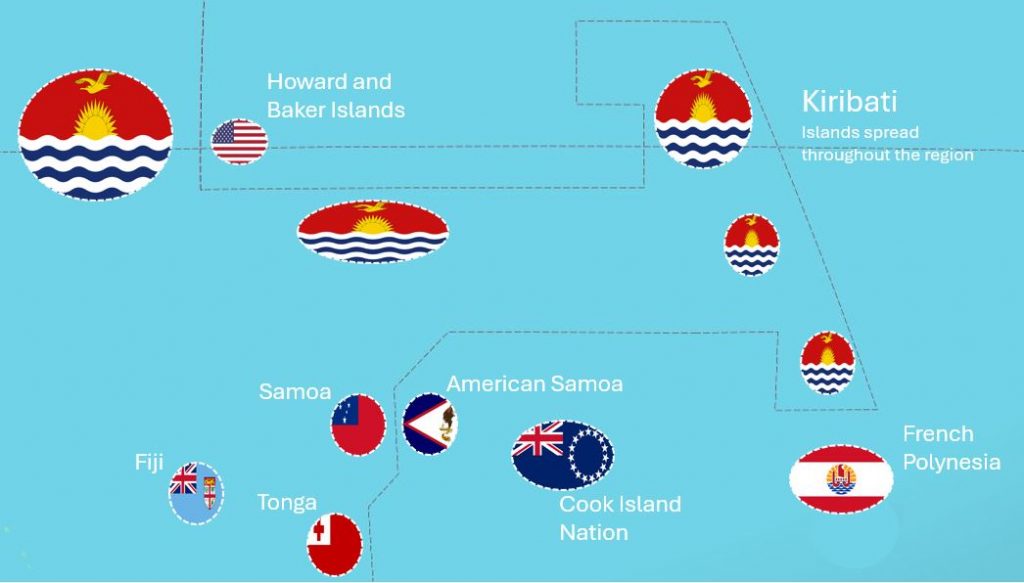

Moving south through the Pacific, over the equator and into the southern hemisphere, we find an increasing concentration of island nations, atolls, archipelagos and overseas territories. These islands have decisions to make in terms of their political and economic allegiances. You might think that being on the same side of the IDL as the USA would be economically advantageous, but this far south in the Pacific, the US mainland is prohibitively distant for such small economies to rely on.

Kiribati: A Country in Two Time Zones

The IDL next approaches the Republic of Kiribati, an island nation spread over a vast area of the central Pacific. Kiribati is an interesting case, it used to be bisected by the IDL, causing significant inconvenience. To address this, in 1995, Kiribati moved the IDL eastward to include the Line Islands within the same time zone as the rest of the country. This shift meant that the Line Islands, previously among the last places on Earth to see the new day, became the first.

The result of this manoeuvre from Kiribati is that the IDL must thread a course keeping the tiny US Howard and Baker islands on its east, cross the equator and take a turn to the east, running parallel with the equator for over 2,000km. It then makes a turn to the north, and once again crosses the equator to encompass the island chains of Kiribati, before returning back to the south and west, all the while ensuring that the islands belonging to the Cook Islands nation and French Polynesia remain on the west of the IDL. The effect is that the IDL forms something resembling a hammerhead shark extending 2977 kilometres to the east that straddles the equator.

Just south of the equator, The IDL returns to roughly 170° and heads south once more. The next islands it encounters are Samoa and American Samoa. In 2011, Samoa made a historic shift by moving west of the IDL to align its time zone more closely with its main trading partners, Australia and New Zealand. This change meant skipping an entire day—December 30, 2011. American Samoa, a U.S. territory, remains east of the IDL, creating a 24-hour time difference between the two Samoas despite their proximity. Fiji, with its blend of Melanesian and Polynesian cultures, lies slightly further to the west and shares a similar time zone as Samoa and Australia.

The IDL runs for the next 3,000km along a longitude of 170°. It maintains this course once again to ensure that an island is not separated from the rest of its home country, in this instance, Chatham Islands and New Zealand. The Chatham Islands, located about 680 kilometres southeast of New Zealand’s main islands, are the most easterly point of New Zealand. They are 45 minutes ahead of New Zealand time. This odd time difference highlights the complexities of aligning local time with the global timekeeping system. Immediately south of the Chatham islands, the IDL returns to its correct longitude of 180° and remains here for the remainder of its journey south.

Finally, the IDL reaches the Southern Ocean and Antarctica. In this remote and icy region, the concept of time zones becomes almost meaningless due to the extreme conditions and the lack of any permanent population. The various research stations scattered across the continent typically use the time zones of their home countries or supply points.

Why the International Date Line Bends

It’s tempting to see these deviations from the exact course that the IDL should take as somehow creating impurity in an otherwise perfect concept of time. But the entire concept of clock time is somewhat contrived and arbitrary. What good is maintaining a perfect concept of an international date line if this then means that islands and nations are split in two? If the arbitrary nature of the IDL causes economic hardship, then why not change it? The bends and deviations of the International Date Line are necessary to maintain practical and convenient time zones for the people living near it. Straightening the IDL would result in adjacent areas being on different calendar days, causing confusion for trade, communication, and travel.

For example, the IDL’s splitting of the Diomede Islands ensures that despite being close, Big Diomede and Little Diomede are in different time zones, maintaining a consistent day-to-day rhythm for their respective countries. The significant bend around Kiribati ensures the entire country shares the same calendar day, simplifying governance and commerce.

The eastward shift around Samoa and American Samoa reflects economic and social ties, with Samoa aligning its time zone to facilitate business with Australia and New Zealand. These adjustments highlight the importance of the IDL in balancing the natural 24-hour day cycle with human activities and interactions.

The real world impacts

The International Date Line profoundly impacts global timekeeping, travel, and communication. For travelers, crossing the IDL can be disorienting as it results in losing or gaining an entire day. This effect is particularly noticeable for those flying across the Pacific Ocean, where a flight from new Zealand could cross the IDL 3 times, twice at American Samoa and again at Kiribati

In terms of communication, the IDL plays a crucial role in coordinating international events and activities. It helps define the sequence of time zones, ensuring that global events, such as New Year’s celebrations, occur in a logical and predictable order. This coordination is essential for international business, media broadcasts, and even personal communications, as people across the world interact around a common understanding of time.

The International Date Line is a fascinating and essential feature of our global timekeeping system. From the icy reaches of the Arctic to the southern expanse of Antarctica, the IDL serves as the boundary where each new day begins. Its bends and deviations reflect the practical needs of the countries and islands it intersects, ensuring that timekeeping remains coherent and functional. It has shaped the relationships shared between the many island nations in the region, and driven global politics for decades. The line is a dynamic and ever changing, offering not a technical measure of clock time but rather a reflection of human relationships.