The Congo River! Second longest river in the world to the Nile, Second largest river by discharge to the Amazon, Second largest river drainage basin area to the Amazon. Second largest rainforest to…the Amazon. You might think that the Congo river is the perennial silver medalist. You might think that there are more interesting rivers around the world, but don’t pity this mighty river. It’s a fascinating body of water full of stories and meaning. It plays a crucial part in the economies and cultures of the regions it runs through, it’s a vital part of the natural world of a great swathe of the African continent. If you’re looking for a record that sets the Congo River apart, then look down. The Congo River is staggeringly deep, it’s by far the deepest river in the world with some very specific geological factors that force the river deep into the earth. Let’s explore!

Formation and History

The Congo River’s formation is a result of tectonic activities causing the uplift of the East African Rift. Here, the African plate has spent the last 25 million years slowly tearing itself in two, the newly formed Nubian plate and Somali plate are sliding apart at around 6-7mm per year. The area is littered with other features of this tectonic activity such as Lake Tanganyika, mount Kilimanjaro, and the Danakil Depression, each of which are fascinating in their own right. The Congo River basin is estimated to have formed over 1.5 million years ago during the Pleistocene epoch when tectonic activity caused the landscape to shift and create the vast drainage basin we see today.

Source and Mouth

The most upstream source of the Congo river is the Chambeshi river. It begins its journey to the Atlantic ocean high up on the Zambian Plateau at an elevation of 1,760m (5,774 feet) above sea level and just 430 miles from the Indian Ocean. The Chambeshi flows through the Bangweulu swamps where it merges with the Luapula River. The Luapula River flows in a northeastern direction before joining the Lualaba, which is sometimes considered the main upper course of the Congo as it contributes by far the greatest share of water by volume at this point of the river’s journey.

The river charts a course due north for the next 1,600km (1,000 miles) through the heart of the Democratic Republic of Congo. In this section of the river, you may think that it will simply run its course all the way to the ocean in a more or less straight line, much like the Nile. However, at the town of Kisangani, almost exactly on the equator, it turns eastward and finally changes its name to The Congo River. From here it takes a giant southwestbound arc across the north of the Democratic Republic of Congo. For roughly 1,000km of this journey the river forms the (somewhat disputed) border between the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Republic of Congo, eventually bisecting the two capitals of Brasserville and Kinshasa. These two cities, formerly the capital cities of the states of French and Belgian Congo, hold the record for the closest capital cities at just one mile apart (we’re not counting Rome and the Vatican!).

The river eventually empties into the Atlantic Ocean at the delightfully named Port of Banana on the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola. Unlike many other rivers of comparable scale, the Congo River doesnt really have much of a mouth to speak of. Look at the Amazon, Mississippi or Nile and you will notice that their mouths spread into broad outflows often hundreds of kilometers across and filled with multiple streams. The Congo River, on the other hand, is a little over 5 kilometers at the point it discharges into the ocean.

Drainage Basin

The drainage basin of the Congo River is penned in by various geographical features. To the north is the Central African Republic, where the watershed takes rivers north and east into the gulf of Guinea or the endorheic basin of Lake Chad. To the northeast, rivers flow mostly into the Nile. To the east, the great Rift Valley forms an impenetrable obstacle, all rivers east of the great rift, such as the Tana in Kenya, the Pagnani in Tanzania eventually find their way into the Indian ocean. To the south a series of mountain ranges, plateaus and highlands in Zambia and Angola force the Congo River northbound. To the northeast, the rivers of Gabon and Cameroon flow directly into the Atlantic Ocean, Gulf of Guinea, or form tributaries of the Niger river.

All in all, this gives the Congo drains an impressive 3,730,881 square kilometers of area in the center of Africa. This is the second largest drainage basin of any river in the world.. At Kinshasa and Brazerville, the flow rate ranges from a high of 65,000 to a low of 21,000 cubic meters. It is estimated (but not confirmed) that a series of floods in 1962 caused flow rates in excess of 73,000 cubic meters which is thought to be the highest flow rate ever down the river.

Widest and Deepest Points

The Congo River is unusual in many ways. It is broadly split into three sections, the upper, mid and lower Congo. The upper Congo consists of all tributaries upstream of the town of Kisangani. As with many river systems, the upper Congo River is interrupted at regular intervals with waterfalls and rapids, including the Boyoma falls at Kisangani. These waterfalls contribute to generally challenging navigability and make the upper Congo unusable for all other than local traffic.

From Kisangani to the Malebo pool is considered the middle Congo. As it meanders down through the Central African republic, it splits and reforms in channels, side channels and branches, sometimes forming islands many miles across. Many of these islands have been settled with permanent populations. This section is entirely free from waterfalls and no significant rapids so is suitable for waterbound traffic connecting the capital cities with towns upstream. Malebo pool itself is the widest point of the Congo at up to 25km wide.

Immediately after Malebo Pool, the Congo River breaks records. Fast! The geology of this area is dominated by particularly old, and particularly hard rock, the sort of rock that water finds difficult to weather away. Rather than try to maintain its impressive width, the Congo narrows drastically. Some parts of the stream are little more than 400 meters wide. Being unable to spread out laterally, and needing to maintain the enormous flow rate out of the Malebo pool, the river found some ancient faults of slightly less tough rock to weather away and simply turned on its side.

Immediately after Malebo Pool, the Congo River breaks records. Fast! At its deepest point, the river reaches a depth of 220 meters. To put that into context, if it were flowing through London, it would cover every building smaller than the Cheesegrater. If you were to be on the very top of the Cheesegrater, and looked across London, you would see just the tops of 5 buildings protruding from the water.

The geology of this area is dominated by particularly old, and particularly hard rock, the sort of rock that water finds difficult to weather away. Rather than try to maintain its impressive width, the Congo narrows drastically. Some parts of the stream are little more than 400 meters wide. Being unable to spread out laterally, and needing to maintain the enormous flow rate out of the Malebo pool, the river found some ancient faults of slightly less tough rock to weather away and simply turned on its side. At its deepest point, the river reaches a depth of 220 meters. To put that into context, if it were flowing through London, it would cover every building smaller than the Cheesegrater. If you were to be on the very top of the Cheesegrater, and looked across London, you would see just the tops of 5 buildings protruding from the water.

This section of river is known locally as the ‘gates of hell’ due to the violent rapids, sudden cascades and complete unnavigability. From here, for the next 320 kilometers to the town of Matadi, the river is so violent, and has so many waterfalls that it is completely unused by any commercial vessels. Inga falls, a little upstream of Matadi, is reckoned to be the waterfall with the largest flow rate in the world, although some say it should be considered a rapids as it falls little more than 96 meters over the course of 15 kilometers.

Unlike other major rivers, where ocean going vessels are able to navigate hundreds or even thousands of kilometers upstream, the Congo River has just two significant inland ports at the towns of Boma and Matadi, just 130km from the mouth of the river. The major cities of Kinshasa and Brasserville have no access to the sea via the Congo. Because of this, the use of the river for regional or international trade is limited. Its primary uses are as a water source, local navigation and as a source of fish for local populations.

Indigenous Peoples

Since its very first flow of water to the ocean, humans have made the riverbank their home. These days, there are thousands of tribes, indigenous communities and distinct cultures that make use of the river and its surrounding ecosystems.

The Bantu peoples are spread throughout the Congo River basin. And have several branches to their community, including:

Bakongo: Living primarily in the western part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), are known for their rich spiritual traditions and vibrant arts.

Baluba: The Baluba are found in the Kasai and Katanga regions. They are renowned for their wooden sculptures and intricate weaving.

Mongo: Inhabiting the central Congo Basin, the Mongo people have a deep connection to the rainforest, relying on it for food, medicine, and cultural practices.

The Pygmy peoples are among the most well-known indigenous populations in the Congo Basin. They are traditionally hunter-gatherers with profound knowledge of the forest. Key characteristics include:

Aka: Found in the northern Congo Basin, the Aka are known for their polyphonic singing and deep understanding of forest ecology.

Mbuti: Inhabiting the Ituri Forest in the DRC, the Mbuti are highly skilled in tracking and hunting and are integral to the forest’s ecological balance.

Twa: Scattered across the Great Lakes region, the Twa are often marginalized but maintain rich cultural practices connected to the forest.

Other peoples and cultures include the Luba and Zande peoples of southeastern DRC, the Ngbandi people of northern DRC, the Mbunda people of Angola and western DRC, and many, many more.

Each of these cultures have vibrant folk law stories and traditions relating to the river. The Bakongo people believe that a spirit called Mami Wata inhabits the river. They depict her as beautiful, with long hair and according to legend, she can bring fortune and misfortune to those who please or displease her.

The Mongo people believe that the land was once arid and lifeless and animals suffered from lack of water. Seeing their plight, a giant serpent called Mboma slithered across the land and carved a deep channel which filled with water. To this day, the Mongo people believe the spirit of Mboma lives in the river and honors the water.

In Luba folklore, there are tales of guardian spirits that protect the Congo River and its surrounding forests. These spirits, known as Bisimbi Bi Masa, are believed to be the ancestral spirits of the river and the land. They are often described as benevolent beings who ensure the river remains bountiful and the forest lush.

Along come the Europeans!

Long after its indigenous populations had created their rich folklore, European exploration of the Congo River began. In the late 15th century, Portuguese navigator Diogo Cão reached its mouth. His mission was part of an all too often repeated story of western European Christians spreading Christianity as far and wide as humanly possible. After Diogo Cão, a veritable armada of Portugese, Spanish, Belgian and British explorers pushed further and further upstream. Pedro de Sousa, Rui de Sequeira, Pedro Quaresma and Gaspar Corte-Real of Portugal, along with David Livingstone of Scotland, Alfred Marche of France, Vernon Lovett Cameron of Great Britain, Alexandre Delcommune of Belgium all Oskar Lenz of Austria and James Kingston Tuckey of Ireland all contributed to the knowledge of geography, geology, hydrology, plant and animal life of the Congo River basin.

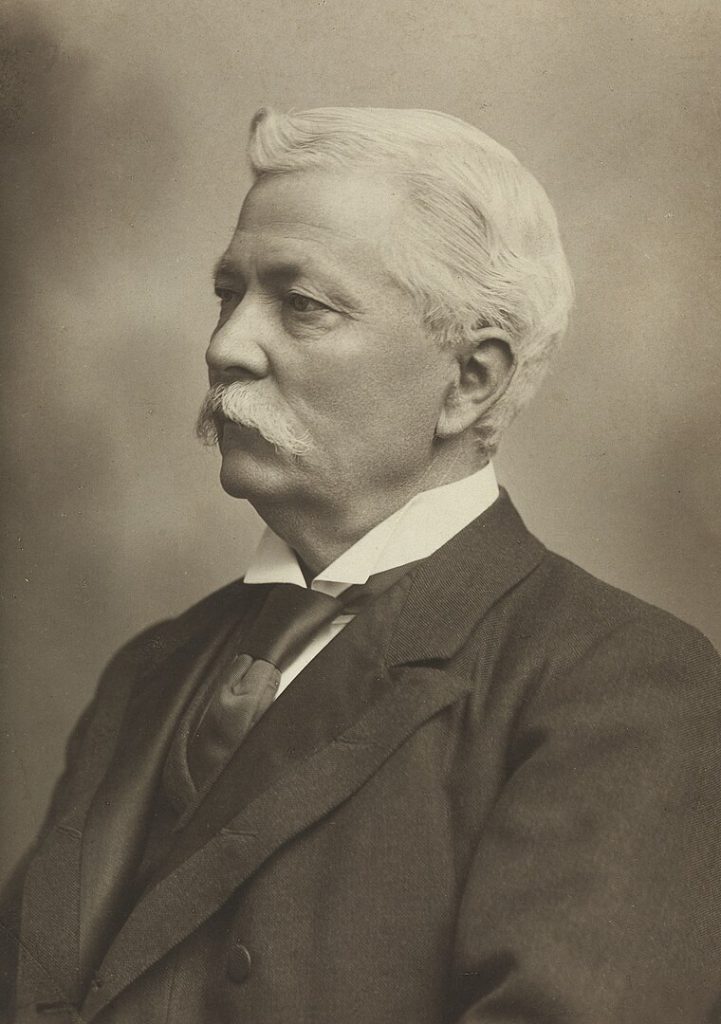

Perhaps the most famous explorer of the Congo River was Henry Morton Stanley. He was born in Denbigh, Wales in 1841 but moved to America, just in time to fight in the American civil war. Luckily, he survived that horror show and was commissioned to chart the course of the Congo river by, of all organisations, the New York Herald and the Daily Telegraph! Morton Stanley had all the usual occupational hazards for 19th century explorers, disease, hostile tribes and generally more difficult terrain than anticipated. He confirmed that the Lualaba was indeed the upper source of the Congo, discovered Boyoma falls, discovered Pool Malebo (which he, rather self-aggrandisingly originally called Stanley Pool) and successfully navigated the rapids and falls of the lower Congo River, eventually reaching the sea in August of 1877.

On the terms set at the time, the mission was a success, however, it came at the expense of brutally violent encounters with many local tribes, ethically questionable methods including bribery and intimidation, and a staggering death rate amongst his own expedition. It is estimated that of the 356 members that embarked on the journey, only 114 reached the sea. He also helped pave the way for the colonialism that would become all too familiar across the entire continent.

The Congo River Today

Despite its importance, the Congo River faces several risks and challenges. Pollution from mining activities, industrial waste, and deforestation threatens the river’s ecosystems and the health of the communities that depend on it. Overfishing and the use of harmful fishing practices also pose a threat to the river’s aquatic life.

Tourism, while beneficial for the economy, has also brought environmental degradation due to not being managed sustainably. The influx of tourists has led to habitat destruction, pollution, and increased pressure on local resources.

Another significant challenge is the political instability and conflict in the region. The region has been brutalized by wars killing thousands, destroying infrastructure and ravaging the natural world. Several of these conflicts are ongoing to this day. Couple the misery of out-and-out wars with the ever real threat of military coups and the impact on economic activity is devastating. Inward investment is simply impossible to attract whilever this level of risk exists. Ensuring the sustainable use of the Congo River requires cooperation between local communities, governments, and international organizations which is simply not possible to achieve in a sustained way in the current climate.

The region has a number of paramilitary forces which are in a near constant state of skirmish. whilst the death toll may be lower than during the Second Congo War, the attacks are a constant reminder of the fragility of the country.

Flora and Fauna

The Congo River basin is home to one of the most biodiverse regions on the planet. The river and its surrounding rainforests is second only to the Amazon rainforest in its scale and variety of plant and animal species. The rainforest covers much of the central and northern basin, and is bordered on all sides by savannah land.

The Congo rainforest is home to trees such as rubber, ebony, mahogany and a variety of palms and ferns. Flowers such as Begonias and epiphytic plants are also common. Plant species such as Acacia, Aloe and the ever evocative Baobab trees can be found in savannah lands surrounding the rainforests. The many wetlands and swampland areas are home to species such as papyrus reed, water lilies and extensive mangrove swamps in the coastal areas. The congo is particularly prevalent in endemic species. Wavy-leaved Ironwood, Camwood and Monopetalanthus are among an estimated tens of thousands of species to be found nowhere else on earth.

Many species in the region are being investigated for their medicinal purposes. Plants such as the root of the Cryptolepis plant may offer antimalarial treatments. The bark of the Yohimbe and the seeds of Bitter kola are both offered in traditional medicines as an aphrodisiac and as treatment to erectile dysfunction.

Animal life in the Congo basin is no less impressive. Large mammals like Forest Elephants, Lowland Gorillas, and primates such as Bonobos, Colobus Monkeys and Mangabeys to various species of Antelope and Buffalo all call this area home. Over 700 species of bird have been recorded with a range of waterbirds such as Herons, Storks and kingfishers native to the river. The surrounding forest hosts species such as the African Grey Parrot, Hornbills and many species of Turacos. Crocodiles, turtles, frogs, toads and a variety of other reptiles and amphibians live in and around the river’s many wetlands and waterways.

Final Thoughts

The Congo River is a vital lifeline for the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the broader Central African region. Its immense size, depth, and biodiversity make it one of the most significant river systems in the world. From its source in the East African highlands to its mouth in the Atlantic Ocean, the river supports diverse ecosystems and provides essential resources for millions of people.

However, the Congo River also faces numerous challenges, including pollution, overfishing, and political instability. Addressing these issues requires concerted efforts to promote sustainable development, protect the environment, and support the livelihoods of local communities. By recognizing the importance of the Congo River and working together to preserve its health and vitality, we can ensure that this remarkable river continues to thrive for generations to come.