There’s something undemocratic at the heart of US democracy. The very ground that the US Capitol building, the Whitehouse, the US Supreme court, the Lincoln and Washington monuments, and all the famous buildings synonymous with US democracy all sit in a city without a voice. The people of Washington DC may be surrounded by the infrastructure of US democracy, but the very proximity to political power means the residents of D.C do not enjoy the same representation as every other American citizen.

In order to make sense of this, we need to head all the way back to the founding of the US itself. In this article we will look at the foundation of this great city, the strategic reasons for its location, its intricate relationship with politics and more specifically, the reasons behind the lack of representation in the US congress.

The Birth of a National Capital

Washington DC is not an old city, even by American standards. Many of the cities that we know and love were founded and thriving long before the establishment of Washington DC. Cities such as Albany and Jersey City had been settled for well over 100 years by the time they broke ground in Washington DC. Philadelphia, which served as the fledgling nation’s capital city on and off throughout the latter part of the 1700s, was the largest city of the 13 colonies with close to 40,000 people. Philadelphia, along with other cities such as Boston and New Amsterdam (soon to be renamed to its more familiar New York) were instrumental in the formation of the US constitution and the first continental congresses in a way that Washington DC simply wasn’t.

With all these thriving metropolises, why bother with a new capital at all? And when exactly did the city come into existence if so much of early American history had already taken place elsewhere? It’s fair to say that this period was rather a busy one in the history of the USA. The 13 colonies had just fought, and won, a bruising and bloody revolutionary war against the British and were in full swing with the crafting of the US constitution. At that time, the 13 colonies thought of themselves almost as independent nations with a shared goal of ridding themselves of the British almost as much as they thought of themselves as a single nation. With this delicate balance in mind, the Founding Fathers sought a neutral location that would not favor any particular state, thereby avoiding regional biases.

The location for the capital was selected by three of the big hitters of US history. President Washington himself, in collaboration with Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. The Residence Act of 1790, signed by President George Washington, authorized the creation of a new capital along the Potomac River. The city was named in honor of George Washington, and “District of Columbia” was chosen to reflect Christopher Columbus. Pierre Charles L’Enfant, a French engineer and architect, was commissioned to design the city, envisioning grand avenues and significant public spaces that would embody the young nation’s aspirations.

Where to put a national capital

The placement of Washington, D.C., along the Potomac River was a strategic decision influenced by several factors. As a matter of principle, the founders believed that the capital should be a federal city, and not beholden to any one state. For this reason, in the very first article of the constitution, the matter of the capital was explicitly settled with section 8 stating that congress shall have the power “to exercise exclusive legislation in all cases whatsoever, over such district (not exceeding ten miles square) as may …..” The clause goes on to talk about cession and other technical matters, suffice to say, the framers of the constitution thought that the independence from local politics of a new capital was very important.

Next up was a point of perception. Alexander Hamilton believed that the US government should be seen in good standing among other nations. The fledgling nation should therefore pay its debts, and by extension, the debts of the 13 founding colonies. This was an issue for the southern states that had paid off their debts and did not want to see the northern states benefit from debt relief. The compromise was for northern states to forego their claim that the capital should continue to be Philadelphia or New York, and the southern states would agree to the federalisation of all debts into the new government. The capital would then be sited in a central location.

The final reason is purely practical, the Potomac River provided a navigable waterway that facilitated trade and transportation. The colonies stretched some 2,100km from Georgia in the south, up the eastern seaboard, to Maine (then a province of Massachusetts) in the north. This at a time when overland travel was in horse drawn carriages. In short, it needed to be central. The proximity to important cities like Baltimore and Philadelphia also made it a convenient choice. Additionally, the land for the new capital was donated by the states of Maryland and Virginia. The new country finally had a political heart!

Planning and construction began almost immediately. The announcement of the site was made by President Washington on January 24th 1791 and the cornerstone of the Whitehouse was laid on October 13th 1792. Just 9 years after the initial building works, the 1800 census showed a population of 8,144. It was a staggeringly successful opening decade. But, I hear you say….what on earth does any of this have to do with a deficit in democracy for the people of Washington DC?

Population explosion

Roll forwards a few hundred years and Washington, D.C. is a melting pot of cultures and ethnicities, reflecting the broader diversity of the United States. The demographic composition includes a significant African American community, making up about 45% of the population. This is followed by White (36%), Hispanic or Latino (11%), and Asian (4%) communities. The city has a population of approximately 678,000 residents. This puts it at around 20th largest city in the modern US but, more interestingly, it makes it larger than the populations of both Vermont and Wyoming and only slightly smaller than Alaska and both the Dakotas.

Because all states are given at least 1 congressional seat and 2 senators, each of the states above enjoy the same benefits of representation as other states. Indeed, some argue that they receive a disproportionate level of representation as the half a million people of Wyoming are represented by the same number of senators as the 38 million people of California.

It’s time to introduce our next character in the story of Washington DC. The congressional delegate to the US house of representatives, Eleanor Holmes Norton. One of the most contentious issues surrounding Washington, D.C., is its lack of full congressional representation. Holmes Norton is a non-voting delegate in the House of Representatives. She can speak on the house floor, introduce legislation and propose amendments, but she does not have the voting power of her fellow Congressmen and women.

This situation stems from the Founding Fathers’ decision to establish a separate federal district that would not belong to any state, thereby ensuring the neutrality of the capital. Herein lies the issue. It’s unclear whether the Framers anticipated a thriving metropolis to grow out of the banks of the Potomac and even less clear what they had in mind for the representation of those that lived within the federal territory.

Taxation without Representation!

This problem has been bubbling along for virtually the entire history of the USA as a country. In February of 1801, just a few months after the creation of the district of Columbia, the residents of the district submitted a statement to congress noting:

“we shall be completely disfranchised in respect to the national government, while we retain no security for participating in the formation of even the most minute local regulations by which we are to be affected. We shall be reduced to that deprecated condition of which we pathetically complained in our charges against Great Britain, of being taxed without representation.”

This lack of representation has sparked debates and movements advocating for “D.C. statehood” or other forms of increased representation. Proponents argue that the district’s residents, who pay federal taxes and serve in the military, deserve the same representation as citizens in the states. The slogan “Taxation without representation,” reminiscent of the Revolutionary War era, has become a rallying cry for these advocates. The phrase is so synonymous with the district that it’s printed on the car registration plates!

Potential Constitutional Remedies

Addressing Washington, D.C.’s lack of representation will inevitably require constitutional and legislative solutions. Several proposals have been put forth over the years, each with its own set of challenges and implications.

Retrocession to Maryland:

One proposal involves returning most of the district’s land to Maryland, while maintaining a small federal district encompassing key government buildings. This idea is not so far-fetched. The original boundary of Washington DC was a perfect square that spanned both the north and south banks of the Potomac. Alexandria and Arlington, both on the south west of the Potomac, Were retroceded to Virginia in 1846. Retrocession would provide residents with congressional representation as part of Maryland, but it faces political and logistical hurdles. Not least among them is the attitude of Washington DC and Maryland residents to the proposal. A 1994 poll showed just 25% supported the proposal of retrocession, in 2000 that number was 21%, 2016 it was 28%. In short, neither the residents of Washington DC, nor the residents of Maryland want retrocession.

Expanded Home Rule:

Expanding the district’s home rule authority could provide more local autonomy and limited congressional representation without full statehood. This would involve granting the district more power to govern itself and potentially providing a voting representative in the House of Representatives. While this approach may be more feasible than statehood or a constitutional amendment, it would still require significant legislative changes.

Constitutional Amendment:

This could come in two forms – the first being simply to grant full congressional representation to the residents of Washington DC. This approach would address the issue directly but would require constitutional amendment with a two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress and ratification by three-fourths of the states, making it a challenging and lengthy process. Amendments to the constitution have become virtually impossible in recent decades due to the hyper-partisan nature of politics. The last to be successfully ratified was the 27th amendment which delays congressional pay rises taking effect until after the subsequent election.

D.C. Statehood:

The second constitutional amendment would be for full statehood. If giving Washington DC residents their own congressional representatives is a hill to climb, then full statehood is the Everest of options! Not only would this give the city a new member of congress, it would also give them two new senators as each state receives two regardless of size or population. The opposition to this proposal can be traced pretty directly back to the demographics of Washington DC. The city leans heavily Democrat. In the 2020 election, it voted 86% for Joe Biden. There is simply no feasible route to getting a majority requiring Republican support. Washington DC’s political leaning virtually guarantees that whilst this amendment may pass through a Democratic controlled house, it will certainly fail to clear the two thirds senate and states as US politics is currently constituted. In other words – its all about the politics

Whilst people were justifiably unhappy with the lack of representation and had protested regularly, things came to a head as a result of the Covid 19 crisis. Up until this point, whilst Washington DC didn’t have the same democratic representation, for all intents and purposes, they were treated as if they were a state. The passage of the 2020 coronavirus relief bill provided a billion dollars to each state in aid. In this same bill, Washington DC was treated as an overseas territory in the same way as Guam or American Samoa and was provided less than half that amount. Couple this with the deployment of US federal troops onto the streets of Washington DC to suppress (or control depending on your political perspective) black lives matter protests, something which would be unconstitutional in any other state of the Union, and the issue was supercharged.

Issues which were objectionable became intolerable. Residents of Washington DC argue that they pay more federal income tax than any other state, yet laws on issues such as same sex marriage, gun laws, drug crimes, abortions and social care have all to a greater or lesser extent been crafted by the direct rule of Republican congresses and are therefore out of step with the heavily Democratic population.

You might ask, how did other states become states? Well the most recent examples were Hawaii and Alaska. They both became states in 1959. At the time, Alaska leaned Democratic and Hawaii leaned Republican so there would be no change to the balance of power. Going further back, states joined the union based on their status of supporting slavery. Texas, a slave state with Wisconsin, a free state. Florida a slave state with Iowa, a free state. Arkansas, a slave state with Michigan, a free state. Missouri, a slave state with Maine, a free state. There has always been an ability to balance power between the two principal parties. The problem for Washington DC? There simply is no other potential state that would maintain this balance. The nearest potential news state would be Puerto Rico, who’s political parties are aligned closer to statehood vs. independence rather than Democratic vs. Republican. Even worse, although a majority of people within Puerto Rico prefer statehood, it would likely vote Democrat. It would appear that even the usual mechanism for statehood would not advance the cause of Washington DC.

Where to draw the line

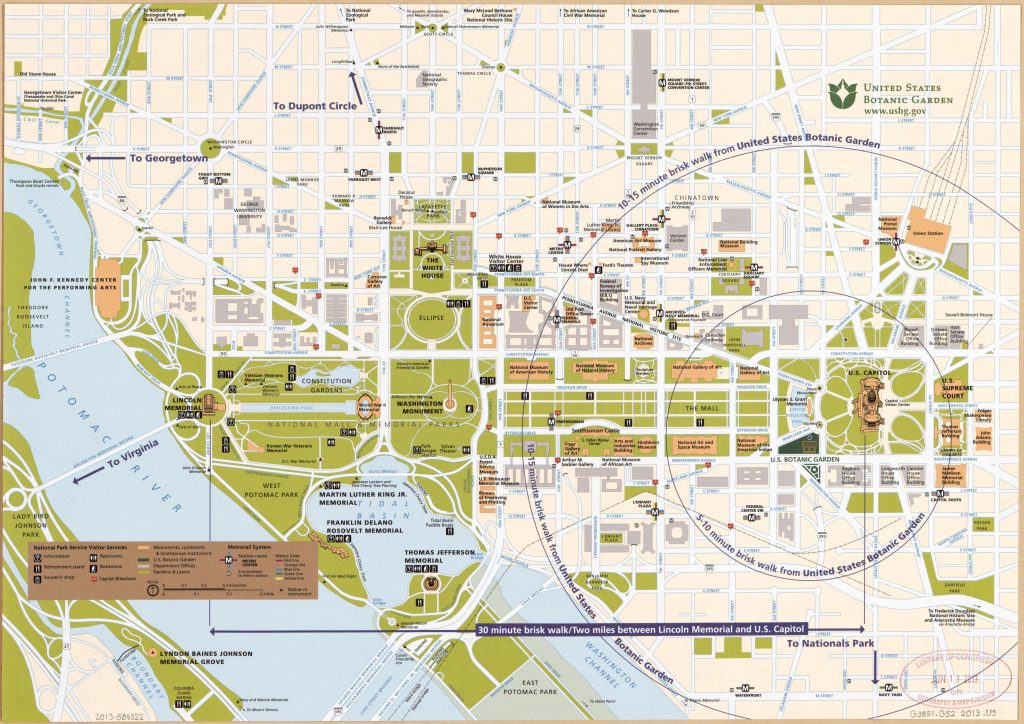

So what’s the answer? Well honestly, no option is a good option for Washington DC. The purists might argue that the only real option would be full statehood. Whether made in good faith or not, the political arguments against Washington DC statehood show no sign of abatement. Even if the stars could align and political consensus be achieved then there is a principled argument about the intention of the founders for the federal government to not be in any one state. I think it’s fairly clear that this federal district must include at the least, the national mall, the Capitol building, the grounds of the Whitehouse, the Lincoln and Washington monuments, the supreme court building, but where would the line be drawn after that? Should the office of the US Attorney General be included? the FBI headquarters? Library of Congress? The Center for Disease Control and Prevention? The Department of Education? NASA headquarters? Bureau of engraving and printing?

If you include the National Museum of African American History and Culture, the Smithsonian, the National Gallery of Art, which all sit along the national mall, should you also include the National Museum of the United States Navy on the banks of the Anacostia River? All of these buildings, and many others spread throughout Washington D.C carry out official federal government business, and they do not occupy a contiguous portion of Washington DC. It is legitimate to ask exactly where do you define the federal district? And how much of Washington DC do you need to include in that district before you compromise the possibility of a state?

Land of the Free?

Whilst all of this constitutional debate is happening, Washington, D.C.’s is thriving. Its economy is robust and diverse, with a GDP of approximately $141 billion, which makes it the 36th largest state economy. It punches above its weight. The federal government is the largest employer, providing a stable economic base for the city which literally cannot go anywhere.

The proximity to government provides a never ending demand for legal services, lobbying, public relations, consulting, hospitality, marketing and every other sort of organisation needed for organisations and individuals to influence US politics.

The city is home to renowned universities such as Georgetown University, George Washington University, and American University, which attract students from around the world. Additionally, prominent healthcare institutions, including MedStar Health and Children’s National Hospital, provide critical services and employment opportunities.

Tourism is another vital industry, fueled by the city’s rich historical heritage and iconic landmarks. Attractions like the National Mall, the Smithsonian museums, the Capitol Building, and the White House draw millions of visitors annually, contributing significantly to the local economy.

It’s an antagonistic question to ask, especially to the freedom minded US people, but does anything need to change? The very reason for the lack of representation is in no small part the same reason that Washington DC is thriving. Washington DC is constitutionally messy and complex. It’s a 250 year old hangover of a decision made by the founding fathers of the United States. In a twisted irony, its fate is in the hands of the officeholders sitting in the very government buildings that cause the problems. How does this end? Your guess is as good as mine!